Fed Rate Hike, what it means, and raising taxes as an alternative

In this week's newsletter, we'll discuss the Federal Reserve raising the rate another 75 basis points and what that means.

📈 Fed Rate Hike

The Federal Reserve announced that it’s raising interest rates by 0.75 percentage point, following its September 20-21 meeting, bumping the federal funds rate to a target range of 3.0 to 3.25 percent. It’s the third consecutive time the Federal Reserve has raised rates 75 basis points.

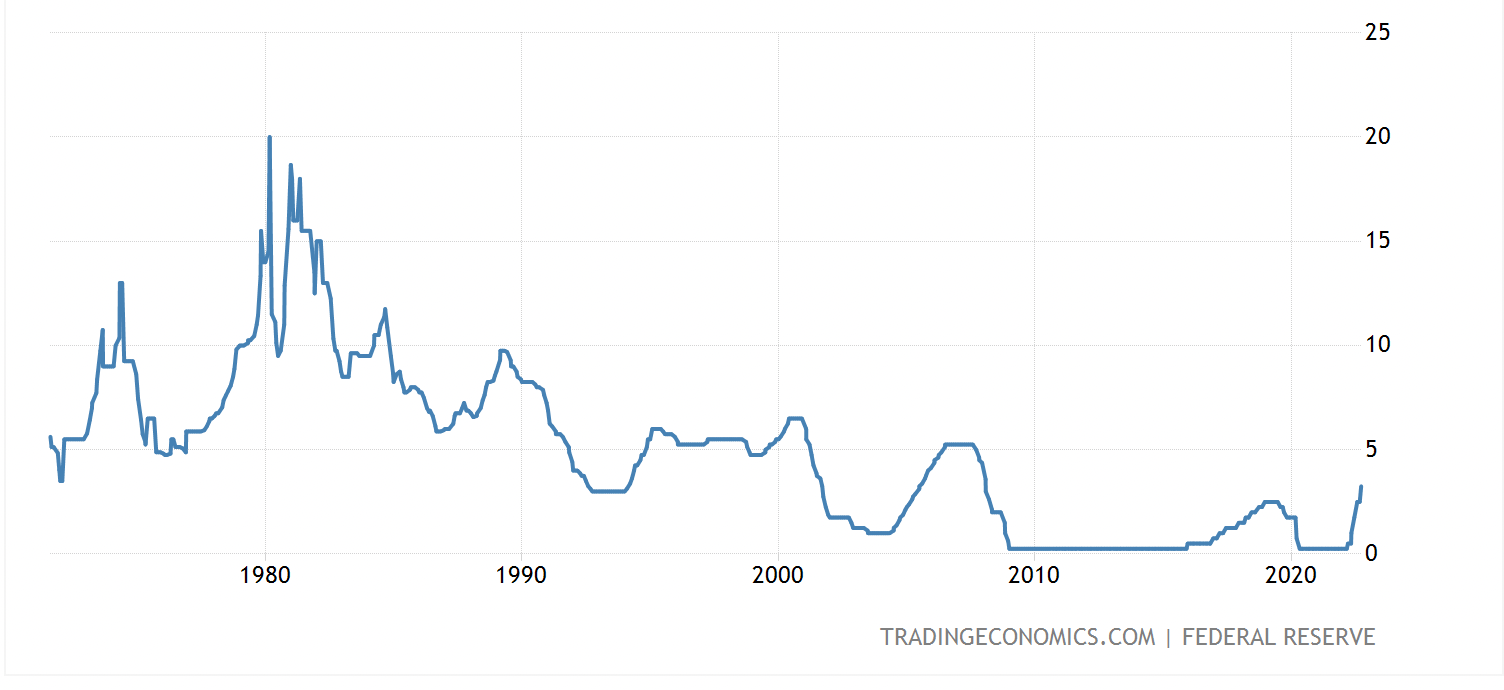

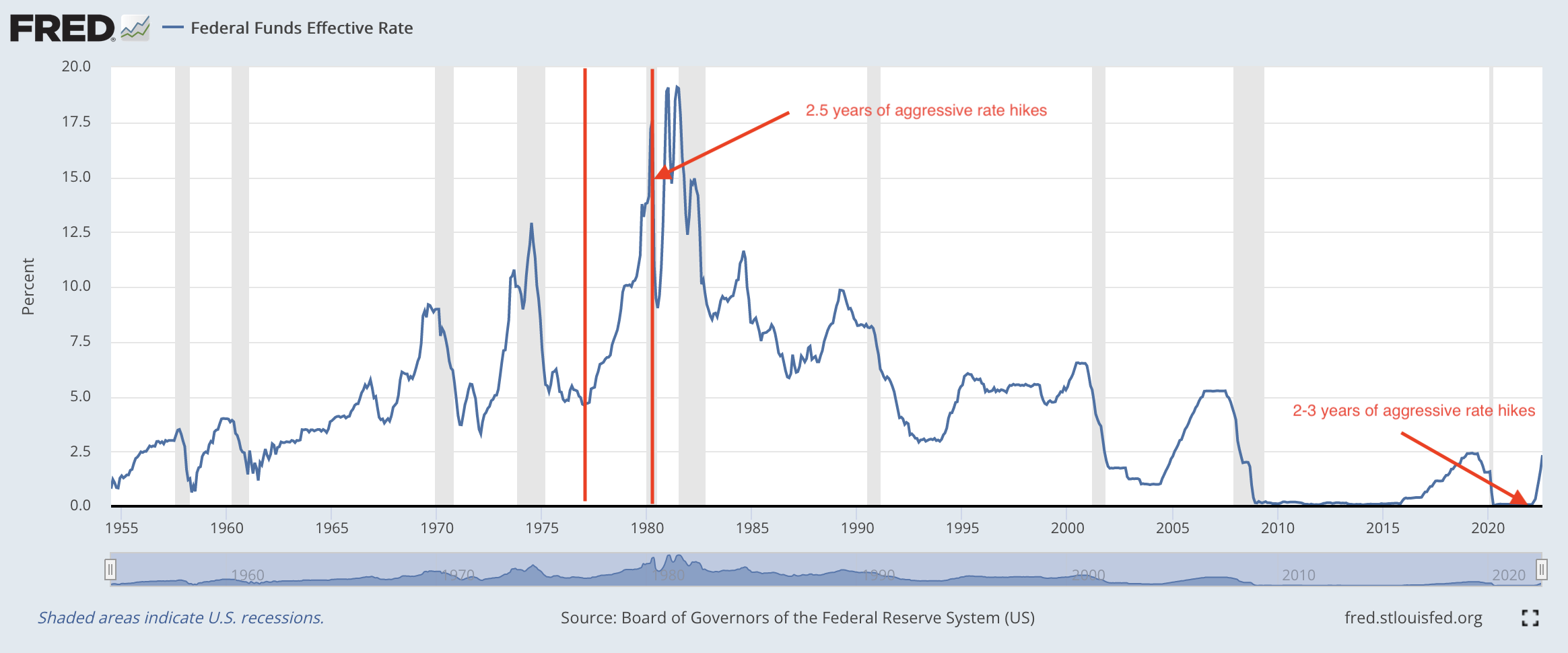

If you look at the current trajectory of Federal Reserve Rates (bottom right corner), the rates are going up aggressively.

With the current inflation situation, we are likely for a 2-3 year period of intense rate hikes. If you look at how these rates rose in the 1970s and 1980s they followed a similar trajectory.

By September 2025, we may see rates between 9-13% for the Federal Reserve Funds Rate.

Here's why:

- Most rate hikes of this scale follow a 2-3 year pattern of steep hikes: If we look at the late 70s and other periods beforehand, most of the rate hikes have been done in a 2-3 year time period.

- Rates were essentially 0 during the pandemic so the correction may need to be steeper to bring down inflation: Moving inflation to where it was before the pandemic will likely take a stronger hand than most people believe.

- Jerome Powell, the current Federal Reserve Chairman, is a strong follower of Volcker's views on Inflation: We'll take a trip down Volcker lane later in this article.

Why does this Federal Reserve Interest Rate matter?

That rate does not directly control rates for mortgages and other loans. But it influences how much banks and other financial institutions pay to borrow, which helps drive loan pricing more broadly. And crucially, the Fed’s own communications — be it remarks from Fed officials or policymakers’ economic projections — are key to shaping financial conditions and getting the markets to start pricing in rate hikes that are still to come. (Washington Post)

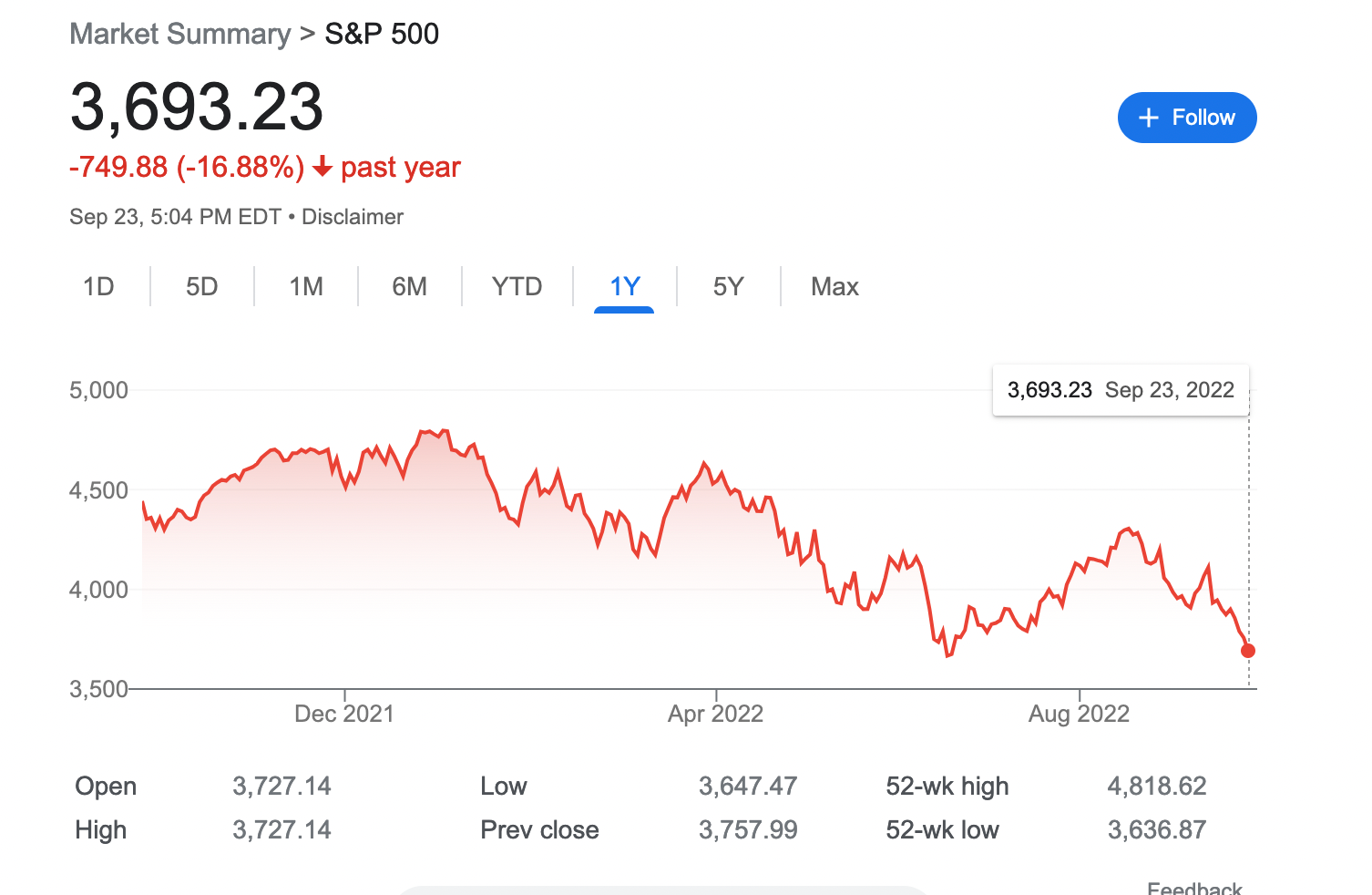

Impact to markets and investor sentiment

We're already starting to see the effects of a market correction with stocks being down significantly. The decline in price affects pensions, livelihoods, and savings.

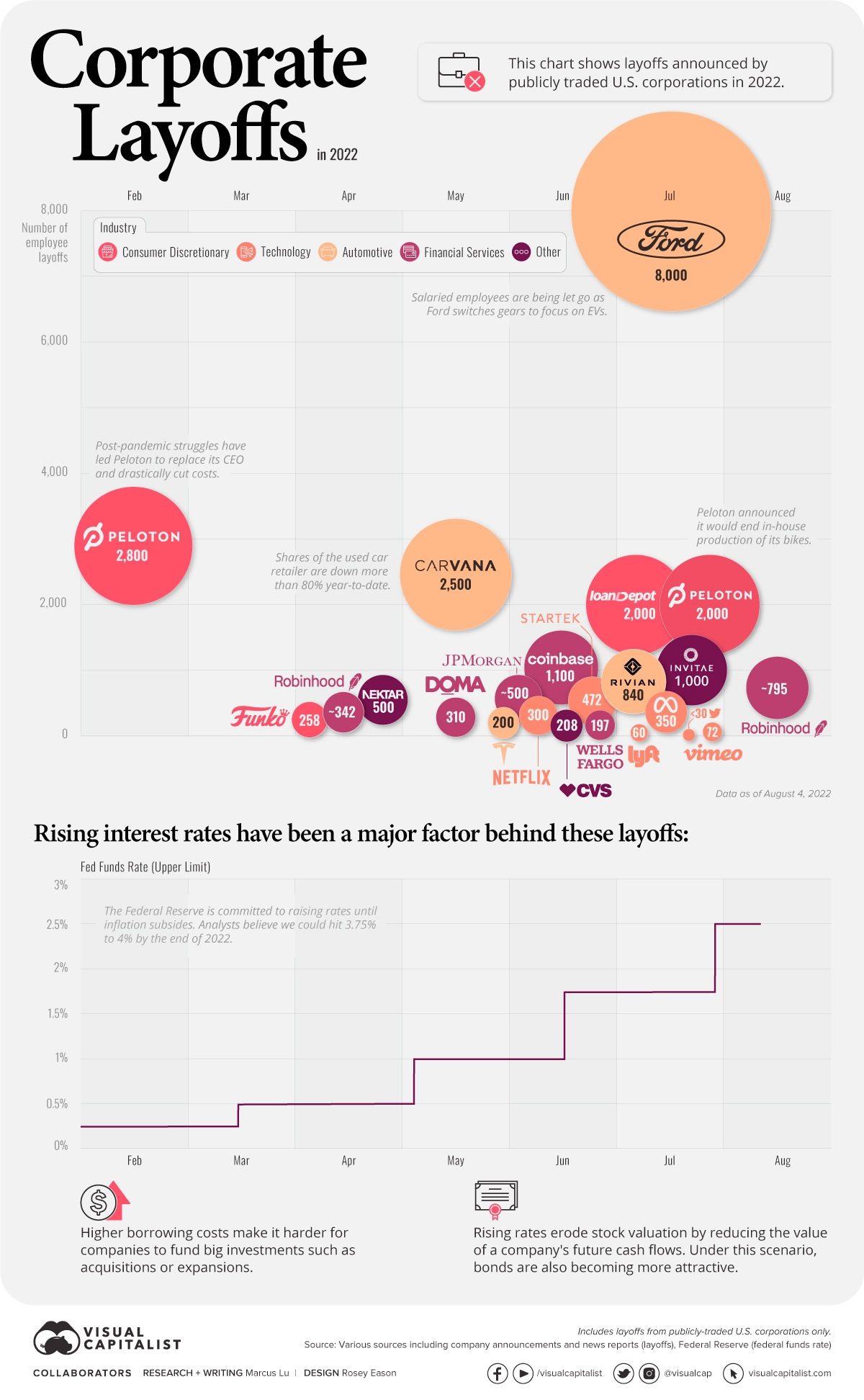

Layoffs

In addition, there is a strong rise in layoffs, especially at larger companies. It's harder for large companies in the growth stage to rely on investor money, so switching profitability requires a shift in strategy and, unfortunately, can result in layoffs.

If the interest rates keep rising, it will likely lead to a larger recession with more layoffs.

A trip down Volcker Lane

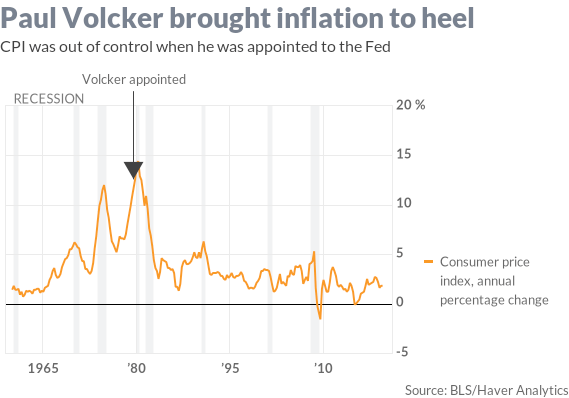

Paul Volcker was appointed chairman of the Fed in August 1979, in large part because of his anti-inflation views.

Volcker presided over the largest rate increases in Fed history and kept them high amidst strong congressional resistance and popular opposition.

However, he managed to bring inflation down.

1981-182 Recession

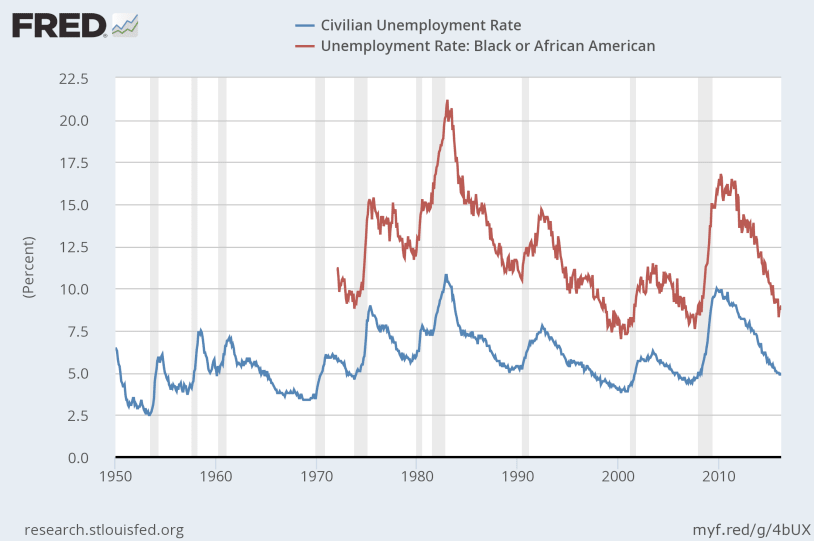

However, the 1981-82 recession was the worst economic downturn in the United States since the Great Depression. We had a nearly 11 percent unemployment rate reached late in 1982 remains the apex of the post-World War II era (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis). Unemployment during the 1981-82 recession was widespread, but manufacturing, construction, and auto industries were particularly affected.

The economy officially entered a recession in the third quarter of 1981, as high interest rates put pressure on sectors of the economy reliant on borrowing, like manufacturing and construction. Unemployment grew from 7.4 percent at the start of the recession to nearly 10 percent a year later. As the recession worsened, Volcker faced repeated calls from Congress to loosen monetary policy, but he maintained that failing to bring down long-run inflation expectations now would result in “more serious economic circumstances over a much longer period of time” (Monetary Policy Report 1982, 67).

By October 1982, inflation had fallen to 5 percent and long-run interest rates began to decline. The Fed allowed the federal funds rate to fall back to 9 percent, and unemployment declined quickly from the peak of nearly 11 percent at the end to 1982 to 8 percent one year later (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Goodfriend and King 2005).

The parallels between the 1980s and now

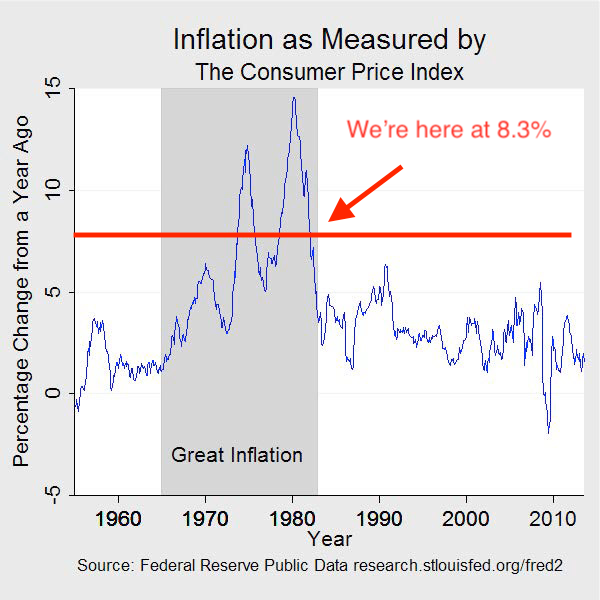

We are living through a similar period in terms of rising inflation.

While I agree with the rate hikes we are doing right now (in other words, it shouldn't be 0), the question for me is how high do we have to go?

How much do we need to increase rates to get the desired effect and outcomes? As we increase rates, there are negative trade-offs and real harm to bring inflation down.

High Unemployment Rates

With the rate hikes, the people that tend to get laid off are the ones with less education, people of color, and the old.

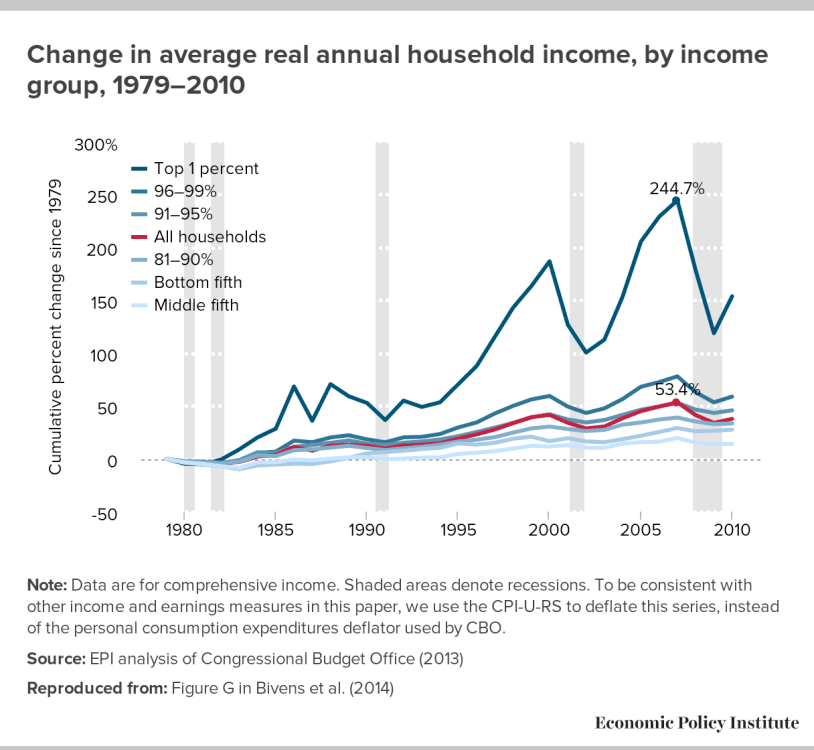

Rise in Inequality

During periods of high rate increases and recessions, inequality greatly increases. The 1% get richer and richer, while those at lower income levels lose household wealth.

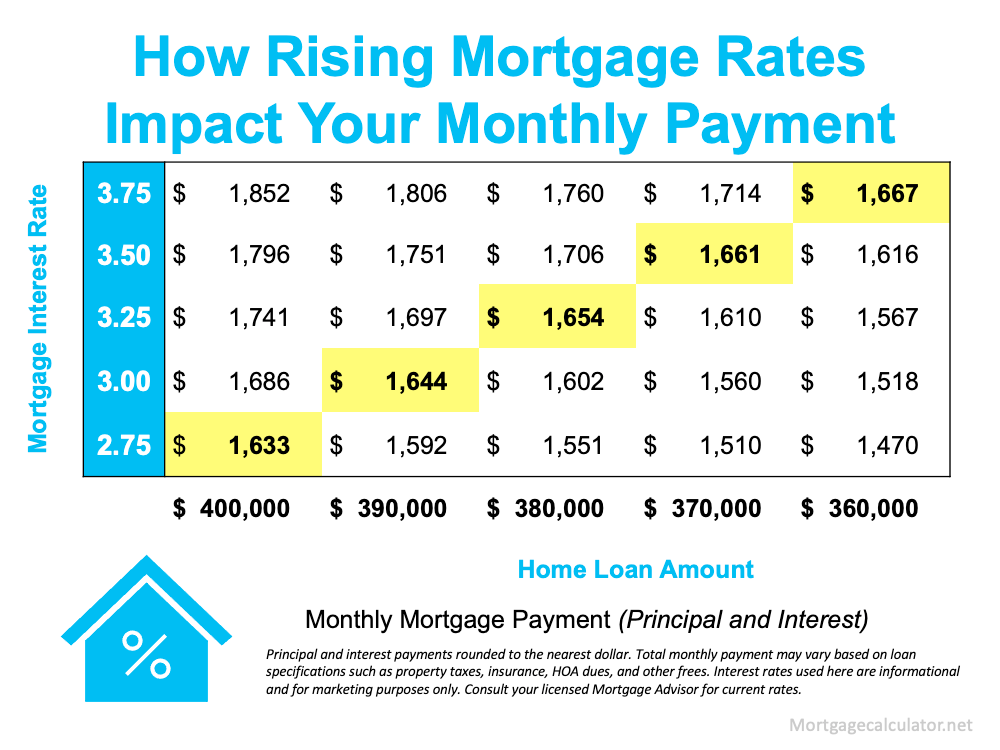

Increase in Mortgage Payments

People will lose houses as the rates increase with increased mortgage payments. Unfortunately, a large number of people do have variable interest rates on their mortgages, and they will go up sharply with the fed raising rates.

Increase Taxes as an alternative to lower the impact of rate hikes

One strategy to lower inflation is to increase taxes. This is a theory by John Maynard Keynes in which raising taxes cools the economy and prevents inflation when there is abundant demand-side growth.

Inflation Reduction Act

Biden has made some progress on this strategy with the Inflation Reduction Act. However, is that enough to lower inflation, or will we have to keep raising interest rates?

Closing Thoughts

Inflation sucks. So does raising the Federal Reserve Funds Rate.

Let me know your thoughts via email or comments. I normally send my newsletter out on Sunday, but I was at the Portola Music Festival on Sunday.

-Oscar